From all that can be learned of him (Patrick), there never was a nobler Christian missionary

(See footnote 1…. He went to Ireland from love to Christ, and love to the souls of men…. Strange that a people who owned Rome nothing in connection with their conversion to Christ, and who long struggled against her pretensions, should be now ranked among her most devoted adherents”

stands out as a creator of civilization. He was not only an architect of European society and the father of Irish Christianity, but he raised up a standard against spiritual wolves entering the fold in sheep’s clothing. So much legend and fiction

I was a free man according to the flesh. I was born of a father who was a decurion. For I sold my nobility for the good of others, and Ido

not blush or grieve about it. Finally, I am a servant in Christ delivered to a foreign nation on account of the unspeakable glory of an everlasting life which is in Christ Jesus our Lord.”

Of the two writings, namely, the Confession, and the Letter, Sir William Betham writes:

In them will be found no arrogant presumption, no spiritual pride,no pretension to superior sanctity, no maledictions of magi, or rivers, because his followers were drowned in them, no veneration for, or adoration of, relics, no consecrated staffs, or donations of his teeth for relics, which occur so frequently in the lives and also in the collections of Tirechan, referring to Palladius, not to Patrick.”

See footnote 7

At the age of sixteen, Patrick was carried captive to Ireland by freebooters who evidently had sailed up the Clyde River or landed on the near-

I, Patrick, a sinner, the rudest and least of all the faithful, and most contemptible to great numbers, had Calpurnius for my father, a deacon, son of the late Potitus, the presbyter, who dwelt in the village of Banavan, Tiberniae, for he had a small farm at hand with the place where I was captured. I was then almost sixteen years of age. I did not know the true God; and was taken to Ireland in captivity with many thousand men in accordance with our deserts, because we walked at a distance from God and did not observe His commandments.”

It can be noticed in this statement that the grandfather of Patrick was a presbyter, which indicated that he held an office in the church equal to that of

CHRISTIANITY IN IRELAND BEFORE PATRICK

Celtic Christianity embraced more than Irish and British Christianity. There was a Gallic (French) Celtic Christianity and a Galatian Celtic Christianity, as well as a British Celtic Christianity. So great were the migrations of peoples in ancient times that not only the

A large number of this Keltic community (Lyons, A.D. 177) —colonists from Asia Minor — who escaped, migrated to Ireland(Erin) and laid the foundations of the pre-Patrick church.”

See footnote 1

The Roman Catholic Church throughout the centuries was able to secure a large following in

Such an independence France had constantly shown, and it may be traced not only to the racial antipathy between Gaul and

See footnote 15Pelagian, but to the fact that western Gaul had never lost touch with its eastern kin.”

PATRICK’S WORK IN IRELAND

Two centuries elapsed after Patrick’s death before any writer attempted to connect Patrick’s work with a papal commission. No pope ever mentioned him, neither is there anything in the ecclesiastical records of Rome concerning him. Nevertheless, by examining the two writings which he left, historical statements are found which locate quite definitely the period in which he labored. When Patrick speaks of the island from which he was carried captive, he calls it “the Britains.” This was the title given the island by the Romans many years before they left it. After the Goths sacked the city of Rome in410, the imperial legions were recalled from England in order to protect territory nearer home. Upon their departure, savage invaders from the north and from the Continent, sweeping in upon the island, devastated it and erased its diversified features, so that it could no longer be called “the Britains.” Following the withdrawal of the Roman legions in 410, the title“the Britains” ceased to be used. Therefore from this

HIS AUTHORITY — THE BIBLE

Patrick preached the Bible. He appealed to it as the sole authority for founding the Irish Church. He gave credit to no

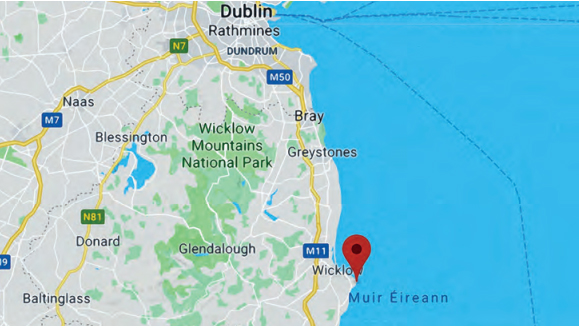

Wherever this Christian leader sowed, he also reaped. Ireland was set on fire for God by the fervor of Patrick’s missionary spirit. Leaving England again with a few companions, according to the record in the Book of Armagh, he landed at Wicklow Head on the southeastern coast of Ireland. Legendary and fabulous is The Tripartite Life of Patrick. It cannot be credited, yet

History loves to linger upon the legend of Patrick’s attack on Tara, the central capital. The Irish, like other branches of the Celtic race, had local chieftains who were practically independent. They also had, by their own election, an overlord, who might be referred to as a king and who could summon all the people when needed for the defense of the nation. For many years Tara had been the renowned capital of Ireland to which were called the Irish chieftains to conduct the general affairs of the realm. These conventions were given over not only to

See footnote 22

The harp that once through Tara’s halls The soul of music shed, Now hangs as mute on Tara’s walls,As if that soul were fled. —So sleeps the pride of former days, So glory’s thrill is o’er; And hearts, that once beat high for praise, Now feel that pulse no more.

It was at the time of one of these assemblies, so the story goes, that Patrick personally appeared to proclaim the message of Christ. The event is so surrounded by legends, many of them too fabulous to be considered, that many details cannot be presented as facts. His success did not come up to his expectations, however; but by faithful

The offender appealed to the pope, who acquitted him over the heads of his superiors. The bishops retaliated by assembling in council and passing a protest forbidding an appeal of lower clergy against their bishops to an authority beyond the sea. The pope replied with resolutions which he claimed had been passed by the Council of Nicaea. Their illegality was exposed by the African prelates.23 Yet it must not be thought, as some writers antagonistic to the Celtic Church claim, that Patrick and his successors lacked church organization.Dr. Benedict Fitzpatrick, a Catholic scholar, resents any such position. He adduces satisfactory proof to show that the Irish founders of Celtic Christianity created a splendid organization.24

THE FICTITIOUS PATRICK

Many miracles have been ascribed to Patrick by the traditional stories which grew up. Two or three will suffice to show the difference between the miraculous hero of the fanatical fiction and the real Patrick. The Celtic Patrick reached Ireland in an ordinary way. The fictitious Patrick, in order to provide passage for a leper when there was no place on the boat, threw his portable stone altar into the sea. The stone did not go to the bottom, nor was it outdistanced by the boat, but it floated around the boat with the leper on it until it reached Ireland.25 In order to connect this great man with the papal see, it was related: “Sleep came over the inhabitants of Rome, so that Patrick brought away as much as he wanted of the relics.

He (Patrick) never mentions either Rome or the pope or hints

See footnote 27tha the was in any way connected with the ecclesiastical capital of Italy. He recognizes no other authority but that of the word ofGod. .. When Palladius arrived in the country, it was not tobe expected that he would receive a very hearty welcome from the Irish apostle. If he was sent by [Pope] Celestine to the native Christians to be their primate or archbishop, no wonder that stout-hearted Patrick refused to bow his neck to any such yoke of bondage.”

About two hundred years after Patrick, papal authors began to tell of a certain Palladius, who was sent in 430 by this same Pope Celestine as a bishop to the Irish. They all admit, however, that he stayed only a short time in Ireland and was compelled to withdraw because of the disrespect which was shown him. One more of the many legendary miracles which sprang from the credulity and tradition of Rome is here repeated. “He went to Rome to have[ecclesiastical] orders given him; and Caelestinus, abbot of Rome, he it is that read orders over him,

WAR ON THE CELTIC CHURCH

The growing coldness between the Celtic and the Roman Churches as noted in the foregoing paragraphs did not originate in a hostile attitude of mind in the Celtic clergy. It arose because they considered that the Papacy was moving farther and farther away from the apostolic system of theNew Testament. No pope ever passed on to the leading bishops of the church the news of the great transformation from heathenism to Christianity wrought by Patrick. This they certainly would have done, as was done in other cases, had he been an agent of the Roman pontiff. One is struck by the absence of any reference to Patrick in theEcclesiastical History of England written by that fervent follower of the Vatican, the Englishman Bede, who lived about two hundred years after the death of the apostle to Ireland. That history remains today the well from which many

no reference whatever to Patrick. The reason apparently is that, when this historian wrote, the Papacy had not yet made up its mind to claim Patrick. When the pope had sent Augustine with his forty monks to convert the heathen Anglo-Saxons, Augustine, with the help of Bertha, the Catholic wife of King Ethelbert of Kent, immediately began

THE CHARACTER OF PATRICK

Patrick, while manifesting all the graces of an apostolic character, also possessed the sterner virtues. Like Moses, he was one of the humblest of men. He revealed that steadfastness of purpose required to accomplish a great task. His splendid ability to organize and execute his Christian enterprises revealed his successful ability to lead. He was frank and honest. He drew men to him, and he was surrounded by a band of men whose hearts God had touched. Such a leader was needed to revive the flickering flames of New Testament faith in the West, to raise up old foundations, and to lay the groundwork for a mighty Christian future. To guide new converts, Patrick ordained overseers or bishops in charge of the local churches. Wherever he went, new churches sprang up, and to strengthen them he also founded schools. These two organizations were so closely united that some writers have mistakenly called them monasteries. The scholarly and missionary groups created by Patrick were very different from those ascetic and celibate centers which the Papacy strove to multiply.32 According to Sir William Betham, monastic life was considered disgraceful by the Scots and the Goths during the first four centuries of the Christian Era.33Among the most famous training colleges which Patrick established were Bangor, Clonmacnoise, Clonard, and Armagh. In Armagh, the most renowned center of Ireland, are located today the palaces of both the Church of England primate and the Roman Catholic primate. Two magnificent cathedrals are there which command attention between them.34One is the cathedral for relics of the Church of Rome, the other for the Church of England. Armagh grew from a small school to a college, then to a university. It is said to have had as many as seven thousand students in attendance at one time. As Ireland became famous for its training centers it acquired the name “Land of saints and scholars.”35 In these

the Scriptures were diligently read, and ancient books were eagerly collected and studied. There are historians who see clearly that the Benedictine order of monks was built upon the foundations so wonderfully laid by the Irish system of education. C. W. Bispham raises the question as to why the Benedictine Rule, a gift of one of the sons of the Papacy, was favored by her, and furthermore, she was jealous of the Celtic Church and crowded out the Bangor Rule.36 Benedict, the founder of the order, despised learning and took no care for it in his order, and his schools never took it up until they were forced to do so about 900, after Charles the Great had set the pace.37 The marvelous educational system of the Celtic Church, revised and better organized by Patrick, spread successfully over Europe until the Benedictine system, favored by the Papacy and reinforced by the state, robbed the Celtic Church of its renown and sought to destroy all the records of its educational system. 38

THE BELIEFS AND TEACHINGS OF PATRICK

In the years preceding the birth of Patrick, new and strange doctrines flooded Europe like the billows of the ocean. Gospel truths, stimulating the minds of men, had opened up so many areas of influence that counterfeiting doctrines had been brought in by designing clergy who strove for the crown while shunning the cross. Patrick was obliged to take his stand against these teachings. The Council of Nicaea, convened in 325 by Emperor Constantine, started the religious controversy which has never ceased. Assembling under the sanction of a united church and state, that famous gathering commanded the submission of believers to new doctrines. During the youth of Patrick and for half a century preceding, forty-five church councils and synods had assembled in various parts of Europe. Of these Samuel Edgar says:

The boasted unity of Romanism was gloriously displayed, by the diversified councils and confessions of the fourth century. Popery, on that as on every other occasion, eclipsed Protestantism in the manufacture of creeds. Forty-five councils, says Jortin, were held in the fourth century. Of these, thirteen were against Arianism, fifteen for that heresy, and seventeen for Semi-Arianism. The roads were crowded with bishops thronging to synods, and the traveling expenses, which were defrayed by the emperor, exhausted the public funds. These exhibitions became the sneer of the heathen, who were amused to behold men, who, from infancy, had been educated in Christianity, and appointed to instruct others in that religion, hastening, in this manner, to distant places and conventions for the purpose of ascertaining their belief.”

See footnote 39

The burning question of the decades succeeding the Council of Nicaea was how to state the relations of the Three Persons of the Godhead: Father, Son, and Holy Ghost. The council had decided, and the Papacy had appropriated the decision

Then the papal party proceeded to call those who would not subscribe to this teaching, Arians, while they took to themselves the title of Trinitarians. An erroneous charge was circulated that all who were called Arians believed that Christ was a created being.41 This stirred up the indignation of those who were not guilty of the charge. Patrick was a spectator to many of these conflicting assemblies. It will be interesting, in order to grasp properly his situation, to examine for a moment this word, this term, which has split many a church and has caused many a sincere Christian to be burned at the stake. In

As volumes have been written in centuries past upon this problem, it would be out of place to discuss it here. It had, however, such profound effect upon other doctrines relating to the plan of salvation and upon outward acts of worship that a gulf was created between the Papacy and the institutions of the church which Patrick had founded in Ireland. While Patrick was anything but an Arian, nevertheless he declined to concur in the idea of “sameness” found in that compelling word “

Patrick beheld Jesus as his substitute on the cross. He took his stand for the Ten Commandments. He says in his Confession: “I was taken to Ireland in captivity with many thousand men, in accordance with our deserts because we walked at a distance from God, and did not observe His commandments.” Those who recoiled from the extreme speculations and conclusions of the so-called Trinitarians believed Deuteronomy 29:29: “The secret things belong unto the Lord our God: but those things which are revealed belong unto us and to our children forever.”The binding obligation of the Decalogue was a burning issue in Patrick’sage. In theory, all the parties in disagreement upon the Trinity recognized the Ten Commandments as the moral law of God, perfect eternal, and unchangeable. It could easily be seen that in the judgment, the Lord could not have one standard for angels and another for men. There was not one law for the Jews and a different one for the Gentiles. The rebellion of Satan in heaven had initiated the great revolt against the eternal moral law. All the disputants over the Trinity recognized that when God made man in His image it was the equivalent of writing the Ten Commandments in his heart by creating man with a flawless moral nature. All parties went a step further. They confessed and denied not that in all the universe there was found no one, neither angel, cherubim, seraphim, man, nor any other creature, except Christ, whose death could atone for the broken law. Then the schism came. Those who rejected the intense, exacting definition of three Divine Persons in one body, as laid down by the Council of Nicaea, believed that Calvary had made Christ a divine sacrifice, the sinner’s substitute. The Papacy repudiated the teaching that Jesus died as man’s substitute upon the cross.

Catholic queen of Scotland, who in 1060 was first to attempt the ruin of Columba’s brethren, writes,“ In this

ENEMIES OF THE CELTIC CHURCH IN IRELAND

An obscurity fails upon the history of the Celtic Church in Ireland, beginning before the coming of the Danes in the ninth century and continuing for two centuries and a half during their supremacy in the Emerald Isle. It continued to deepen until King Henry II waged war against that church in 1171 in response to a papal bull. The reason for this confusion of history is that when Henry II mined both the political and the ecclesiastical independence of Ireland he also destroyed the valuable records which would clarify what the inner spiritual life and evangelical setup of the Celtic Church was in the days of Patrick. Even this, however, did not have force enough to blur or obscure the glorious outburst of evangelical revival and learning which followed the work of Patrick. Why did the Danes invade England and Ireland? The answer is found in the terrible wars prompted by the Papacy and waged by Charlemagne, whose campaigns did vast damage to the Danes on the Continent. Every student knows of that Christmas Day, 800, when the pope, in the great cathedral at Rome, placed upon the head of Charlemagne the crown to indicate that he was emperor of the newly created Holy Roman Empire. With battle-axin hand, Charlemagne

continuously waged war to bring the Scandinavians into the church. This embittered the Danes. As they fled before him, they swore that they would take vengeance by mining Christian churches wherever possible, and by slaying the clergy. This is the reason for the fanatical invasion by these Scandinavian warriors of both England and Ireland.49 Ravaging expeditions grew into organized dominations under famousDanish leaders. Turgesius

landed with his fleet of war vessels on the coast of Ireland about the year 832. He sailed inland so that he dominated the east, west, and north of the country. His fleets sacked its centers of learning and mined the churches. How did the Danes succeed in overthrowing the Celtic Church? It was by first

its designs upon the independence of the Irish Church in the course of the eleventh and twelfth centuries.”50 When the Danish bishops of Waterford were consecrated by the see of Canterbury, they ignored the Irish Church and the successors of Patrick, so that from that time on there were two churches in Ireland.51Turgesius was the first to recognize the military advantages and the desirable contour of the land on which the city of Dublin now stands. With him began the founding of the city which expanded into the kingdom of Dublin. Later on, a bishopric was established in this new capital, modeled after the papal ideal. When the day came that the Irish wished to expel their foreign conquerors, they were unable to extricate themselves from the net of papal religion which the invaders had begun to weave. This leads to the story of Brian Boru.

BRIAN BORU OVERTHROWS THE DANISH SUPREMACY

The guerilla fights, waged for decades between the native Irish and their foreign overlords, took on the form of

THE RUIN OF PATRICK’S CHURCH

Showing that the introduction of the Papacy into England under the monk Augustine was religious and that full power was not secured by Rome until William the Conqueror (A.D. 1066), Blackstone says:

This naturally introduced some few of the papal corruptions in point of faith and doctrines; but we read of no civil authority claimed by the pope in these kingdoms until the era of the Norman conquests, when the then reigning pontiff having favored DukeWilliam in his projected invasion by blessing his host and consecrating his banners, he took that opportunity also of establishing his spiritual encroachments, and was even permitted so to do by the policy of the conqueror, in order more effectually to humble the Saxon clergy and aggrandize his Norman prelates; prelates who, being bred abroad in the doctrine and practice of slavery, had contracted a reverence and regard for it, and took a pleasure in riveting the chains of a freeborn people.”

See footnote 52

The bull of Pope Adrian IV issued to King Henry II of England, 1156, authorized him to invade Ireland. A part of the bull reads thus: “Your highness’s desire of esteeming the glory of your name on earth, and obtaining the record of eternal happiness in heaven, is laudable and beneficial; inasmuch as your intent is, as a Catholic prince, to enlarge the limits of the church, to decree the truth of the Christian faith to untaught and

Several things are clear from this bull. First, in specifying Ireland as an

untaught and rode nation, it is evident that papal doctrines, rites, and clergy had not been dominant there. Second, in urging the king “to enlarge the limits of the church,” the pope confesses that Ireland and its Christian inhabitants had not been under the dominant supremacy of the Papacy. Third, in praising Henry’s intent to decree the Christian faith of the Irish nation, Pope Adrian admits that papal missionaries had not carried theRomish faith to

Ireland before this. In laying upon Henry II the command that he should annex the crown of Ireland upon condition that he secure a penny from every home in Ireland as the pope’s revenue,53 it is clear that the Papacy was not the ancient religion of Ireland and that no Roman ties had bound that land to it before the middle of the twelfth century.W. C. Taylor, in his History of Ireland, speaking of the synod of Irish princes and prelates which Henry II summoned to Cashel, says, “The bull of Pope Adrian, and its confirmation by [Pope] Alexander, were read in the assembly; the sovereignty of Ireland granted to Henry by acclamation;and several regulations made for increasing the power and privileges of the clergy, and assimilating the discipline of the Irish Church to that which theRomish see had established in Western Europe.”54From that time to the Reformation, the Celtic Church in Ireland was in the wilderness experience along with all the other evangelical believers in Europe. Throughout the dreadful years of the Dark Ages many individuals, in churches or groups of churches,

FOOTNOTES/SOURCES:

1.Maclauchlan, Early Scottish Church, pp. 97, 98.

2 Neander, General History of the Christian Religion and Church, vol. 1,sec. 1, pp. 85, 86; Moore, The Culdee Church, pp. 15-20.

3 Ridgeway, The Early Age of Greece, vol. 1, p. 369.

4 Neander, General History of the Christian Religion and Church, vol. 2

5 Gibbon, Decline

6 Smith and Wace, A Dictionary of Christian Biography, art. “Patricius.”

7 Betham, Irish Antiquarian Researches, vol. 1, p. 270.428

8 See Chapter 6, entitled, “Vigilantius, Leader of the Waldenses.”

9 Stokes, Ireland

10 Gordon, “World Healers,” pp. 48, 49.

11 Bidez and Cumont, Les Mages Hellenises, vol. 1, p. 55. For

12 Stokes, Ireland and the Celtic Church, p. 173.

13 Moore, The Culdee Church, p. 2114 Yeates, East Indian Church History, p. 226 (included in Asian Christology and the Mahayana, by E. A. Gordon).

15 Warner, The Albigensian Heresy, vol. 1, p. 20.

16 Stokes, Ireland and the Celtic Church, p. 93.

17 Tymms, The Art of Illuminating as Practiced in Europe From

18 Jacobus, Roman Catholic and Protestant Bibles Compared, p. 4.

19 Neander, General History of the Christian Religion and Church, vol. 3,p. 53.

20 Todd, St. Patrick, Apostle to Ireland, p. 377.

21 Michelet, History of France, vol. 1, p. 74; vol. 1, p. 184, ed. 1844.

22 Moore, Irish Melodies, p. 6.

23 Foakes-Jackson, The History of the Christian Church, p. 527.

24 Fitzpatrick, Ireland and the Making of Britain, p. 231.

25 Stokes, Chronicles

26 Stokes, Chronicles

27 Killen, Ecclesiastical History of Ireland, vol. 1, pp. 12-15.

28 Stokes, Chronicles

29 d’Aubigne, History of the Reformation, vol. 5, pp. 41, 42.

30 See the author’s discussion in Chapter 11, entitled, “Dinooth and the Church in Wales.”429

31 See the author’s discussion in Chapter 12, entitled, “Aidan and the Church in England.”

32 M’Clintock and Strong, Cyclopedia, arts. “Columba” and“Columbanus.”

33

34 The writer when visiting Armagh noted the sites traditionally connected with the life of Patrick.

35 Killen, The Old Catholic Church, p. 290.

36 Bispham, Columban — Saint, Monk, Missionary, pp. 45, 46; Smith and Wace, A Dictionary of Christian Biography, art. “Columbanus.”

37 Stillingfleet, The Antiquities of the British Churches, vol. 1, p. 304.39.

38 Fitzpatrick, Ireland and the Making of Britain, pp. 47, 185.

39 Edgar, The Variations of Popery, p. 309.

40 The Catholic Encyclopedia, art. “Arianism.”

41 It is doubtful if many believed Christ to be a created being. Generally, those evangelical bodies who opposed the Papacy and who were branded as Arians confessed both the divinity of Christ and that Hewas begotten, not created, by the Father. They recoiled from other extreme deductions and speculations concerning the Godhead.

42 Robinson, Ecclesiastical Researches, p. 183.

43 Stokes, Ireland and the Celtic Church, p. 12.

44 Todd, St. Patrick, Apostle to Ireland, p. 390.

45 Newell, St. Patrick, His Life and Teaching, p. 33, note 1.

46 Flick, The Rise of the Medieval Church, p. 237.

47 Barnett, Margaret of Scotland: Queen and Saint, p. 97.

48 Bede, Ecclesiastical History of England, b. 3, ch. 4.

49 Stokes, Ireland and the Celtic Church, p. 252.

50 Stokes, Celtic Church in Ireland, p. 277.

51 Ibid

52 Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England, b. 4, ch. 8, p. 105.

53 O’Kelly, Macariae Excidium or The Destruction of Cyprus, p. 242.430

54 Taylor, History of Ireland, vol. 1, pp. 59, 60.