The return from the captivity, which Cyrus authorized almost immediately after the capture of Babylon, is the starting point from which we may trace

See footnote 1a gradual enlightenment of the heathen world by the dissemination of Jewish beliefs and practices.

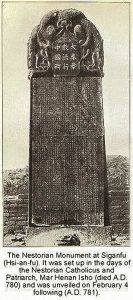

THE NAME OF ADAM singles out an unusual leader whose history is connected with the Church of the East in China. When he was director of the Assyrian Church in China, a memorial in marble was erected in that land in 781 to the praise of God for the glorious success of the apostolic church. From the time that it was excavated in 1625 it has stood as one of the most celebrated monuments of history. The events which led to its erection and the story told by its inscription reveal the early missionary endeavors which carried the gospel to the Far East. When the Spirit of God moved upon the heart of Adam, director of the Assyrian Church in China, and his associates to erect this revealing witness, New Testament Christianity had for some time been shining brightly there. The fact that these missionaries possessed sufficient freedom to plant this remarkable memorial in the heart of the empire, when in Europe the father of Charlemagne was destroying the Celtic Church, shows a remarkable existence of religious liberty in the Orient. Itfurthermore discloses that the Church of the East was large and influentialenough to execute so striking a

project. To indicate how great a statesman Adam was and how strong he was in 781 in the circles of influence in the Chinese, Japanese, and Arabian Empires, let the following facts testify: He was a friend of the Chinese emperor who ordered the erection of the famous stone monument; of Duke Kuo-Tzu, mighty general and secretary of state, who defeated the dangerous Tibetan attack; of Dr. Issu, Assyrian clergyman, loaded with state honors for his brilliant work; of Kobo Daishi, greatest intellect in Japanese history; of Prajna, renowned Buddhist leader and Chinese teacher of Kobo Daishi; of Lu Yen, celebrated founder of the powerful Chinese religious sect known as the Pill of Immortality; of the Arabian court where Harun-al-Rashid, most mighty of the Arabian emperors, had just secured the services of an eminent Assyrian church educator to supervise Harun’snew imperial school system

Politically China was at this moment perhaps the most powerful, the most advanced, and the best-administered country in the world

See footnote 4. in every material aspect of the life of aCertainly state shewasoverwhelmingly superior to Japan. The frontiers of her empire stretched to the borders of Persia, to the Caspian Sea, and to the Altai Mountains. She was in relations with the peoples of Annam, Cochin China, Tibet, the Tarim basin, and India; with the Turks, the Persians, and the Arabs. Men of many nations appeared at the court of China, bringing tribute and merchandise and new ideas that influenced her thought and her art. Persian and, more remotely, Greek influence is apparent in much of the sculpture and painting of the T’ang period. There had since the days of the Wei emperors been friendly intercourse between China and Persia, a Zoroastrian temple was erected in Chang-an in 621…It would be too much of a digression to go on to speak of the paintings, the bronzes, the pottery, the colored silks, the poemsand the fine calligraphies. It is enough to say that all these arts were blossoming inprofusion, when the first Japanese missions found themselves in the T’ang capital. And what perhaps impressed them more than the quality of Chinese culture was its heroic dimensions. Nothing but was on a grand, a stupendous scale. When the Sui emperor builds a capital, two million men are settowork . His fleet of pleasure boats on the Yellow River is towed by eighty thousand men. His caravan when he makes an Imperial Progress is three hundred miles long. Hisconcubines number three thousand. And when he orders the compilation of an anthology, it must have seventeen thousand chapters. Even making allowance for the courtly arithmetic of official historians, these are enormous undertakings; and though the first T’ang emperors were rather less immoderate, they did nothing that was not huge or magnificent. To the Japanese it must have been staggering.

The famous monumental stone now stands in the Pei Lin (forest of tablets)in the western suburb of Changan.5 It was set up by imperial direction to commemorate the bringing of Christianity to China. Dug out of the ground by accident in 1625, where it evidently had lain buried for nearly a thousand years, this marble monument ranks in importance with the Rosetta stone of Egypt or the Behistun inscription in Persia. It has engraved upon it 1,900 Chinese characters reinforced by fifty Syriac words and seventy names in Syriac. The mother tongue of the Christian newcomers and the official tongue of the Assyrian Church was Syriac

How great was the degree of civilization in these days throughout central Asia and the East may be seen in the following quotation from a recognized author:

With unexampled honors, Kao-Tsung and his empress received back to China, in 645, The Prince of Pilgrims, Huen T

See footnote 8’sang , after his sixteen years’ pilgrimage of over 100,000 miles to Fo-de-fang,the Holy Land of India, in search of precious sutras and “the true,good law,” finding everywhere, among the tribes of central Asia,the highest degree of civilization and religious devotion.

Hsuan Tsang was beginning his research journey just after Columbanus had finished his glorious labors. The Celtic Columbanus, however, carried his Bible with him as he journeyed east, while Hsuan Tsang traveled west from his native China to obtain the scriptures of Buddha in India. Many who have written about this great stone mistakenly call it the Nestorian monument. The word “Nestorian” is nowhere found on it. In fact, the inscription has no reference whatever to either Nestorius orNestorians. Moreover, it does explicitly recognize the head of the Church of the East by giving the name and the date of the patriarch of Bagdad, Persia, who at that time was

states, was ruled by the Tang dynasty. Between these lay the mighty Arabian Empire. The most famous emperor in the history of this Arabian imperium was Harun-al-Rashid.

There was much to facilitate the contact between Persia and China at this time. Most of the nations lying between them were well populated. Travel was frequent, the highways were well cared for, and an abundance of vehicles and inns to facilitate merchants and tourists was at hand

DID CONFUCIUS COUNTERFEIT DANIEL’S RELIGION?

About five hundred years before the commencement of the Christian Era a great stir seems to have taken place in Indo-Aryan, as in Grecian minds, and indeed in thinking minds everywhere throughout the then-civilized world. Thus when Buddha arose in India, Greece had her thinker in Pythagoras, Persia, in Zoroaster, and China in Confucius.

See footnote 12

In a former chapter it was stated that within a hundred years after the death of the prophet Daniel, Zoroastrianism flourished in Persia, Buddhism rose in India, and Confucianism began in China.(13) From Pythagoras, possibly a pupil of Zoroaster, philosophy had obtained its grip upon Greece. According to the dates generally assigned to Daniel and Confucius, the founder of Confucianism was about fourteen years of age when the great prophet died. There is a striking similarity between parts of the philosophy of Pythagoras and that of Confucius. A quotation from a well-known author will show the close relationship between Buddhism and Confucianism:

It is related that a celebrated Chinese sage, known as ‘thenobleminded Fu,’ when asked whether he was a Buddhist priest, pointed to his Taoist cap; when asked whether he was a Taoist,pointed to his Confucianist shoes; and finally, being asked whether he was a Confucianist, pointed to his Buddhist scarf.”

See footnote 14

As the Jews had been dispersed throughout all nations, the stirring prophecies of Daniel were disseminated everywhere. These led all peoples to look with hope for the coming of the great Restorer. The Magi who journeyed from the East to worship at the Savior’s

missionaries of that date. He and his scholars were well aware of the remarkable events which crowded the history touching the Church of the East. The Chinese were not ignorant of the expansion of Christianity among the nations of central Asia. Furthermore, it is not without

Many of those Israelites whom God dispersed among the nations, by means of the Assyrian and Babylonian captivities, found their way to China, and were employed (says the celebrated chroniclerPere Gaubil) in important military posts, some becoming provincial governors, ministers of state, and learned professors. Pere Gaubil states positively that there were Jews in China during the fighting states period, i.e., 481-221 B.C.

See footnote 20

Thus we know that China in Daniel’s day was in contact with the Old Testament religion. According to Spring and Autumn, a book compiled by Confucius himself in 481 B.C., notice is taken of the frequent arrival of “the white foreigners.” Saeki thinks that these could be from the plains of Mesopotamia. The vigorous earlier Han dynasty (206 B.C. to A.D. 9) carded its conquests far to the west and to the Babylonian plains

Returning to the discussion of the Old Testament teachings in China long before Christ, it may be seen that the teachings of the Old Testament came to China not only by way of

“is nothing now to be seen but a vast desert; all

has been buried in the sands.” (26)

It was centuries after the Christian Era before these cities began to disappear.27In Turkestan the road to China was flanked by many cities; consequently, the roads had so many travelers that no one had

Parallel with the decline of the old Semitic idolatry was the advance of its direct antithesis, pure spiritual monotheism. The same blow which laid the Babylonian religion in the dust struck off the fetters from Judaism…. The return from the captivity, which Cyrus authorized almost immediately after the capture of Babylon, is the starting point from which we may trace a gradual enlightenment of the heathen world by the dissemination of Jewish beliefs and practices.

See footnote 29

While these three founders of new religions — Zoroaster, Buddha, and Confucius — were willing to borrow from a cult earlier than their own, it is evident that in order to escape the charge of copying, they would want their own system not to be a duplication of the one from which they borrowed. There is sufficient basis in the teachings of Confucius to conclude that he, like Buddha and Zoroaster, was stimulated enough by the new light shining in the west to launch a religious system of his own. The fundamental truth of the Supreme Being was impressed so powerfully upon Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, and Confucianism that in the establishing of their schemes of religion, they maintained one chief deity. The elimination of lesser divinities in favor of one God over all, such as the OldTestament had taught for centuries, won immediate favor with the masses. One more point will be presented as

According to the Zend-Avesta, the God Ormuzd (Adam or Noahdeified), created the world at six different intervals, amounting in all to a whole year; man, in almost exact conformity with the Mosaic account, being created in the sixth period. The Etrurians state thatGod (Adam or Noah) created the world in six thousand years; man alone

See footnote 30being created in the sixth millenary. Eusebius mentions several of the ancient poets who attached a superior degree of sanctity to the seventh day. Hesiod and Homer do so, and alsoCallimachus and Linus. Porphyry says that the Pheniciansdedicated one day in seven to their god Cronus (Adam appearing in Noah). Aulus Gellius states that some of the heathen philosophers used to frequent the temples on the seventh day; Lucian mentions the seventh day as a holiday. The ancient Arabians observed a Sabbath before the era of Mohammed. The mode of reckoning by “seven days,” prevailed alike amongst the Indians, the Egyptians, the Celts, the Sclavonians, the Greeksand the Romans. Josephus then makes no groundless statement when he says, ‘there is not any city of the Grecians, nor any of the barbarians, nor any nation whatsoever, whither our custom of resting on the seventh day hath not come!’ Dion Cassius deduces this universal practice of computing by weeks from the Egyptians, but he should have said from the primitive ancestors of the Egyptians, who were equally the ancestors of all mankind. Theophilus of Antioch states as a palpable fact, that the seventh day was everywhere considered sacred; and Philo (apud Grot. et Gale) declares theseventh day to be a festival, not of this or of that city, but of the universe.

Especially to be noted in the above citation is the reckoning by seven days not only in India, but also among the Celts, Slavs, Greeks, and Romans. Homer and Hesiod, who lived about the ninth and eighth centuries beforeChrist, are included in those believing in the sacredness of the seventh day. Such was the powerful influence of the Old Testament

“They keep the Sabbath quite as strictly as do the Jews in Europe.” (31)

If honoring the seventh day was true among the ancient inhabitants of the land of Chaldea, from which it is asserted that the ancestors of the Chinese came, it was also prominently true in ancient China. A passage from one of the classical works of Confucius, written about 500 B.C., is as follows:

“The ancient kings on this culminating day (i.e., the seventh) closed their gates, the merchants did not travel and the princes did not inspect their domains.” (32) Charles de Harlez adds, “It was a sort of a day of rest.”(33)

All the

CHRISTIANITY’S EARLY GROWTH IN CHINA

At the time of the erection of the celebrated stone monument, missionaries of Adam’s faith had penetrated everywhere throughout central Asia, and already possessed multiplied churches in China. How far these evangelists had spread the knowledge of Adam’s mother tongue, the Syriac, may be gathered in the following words of Ernest Renan:

It will be seen what an important

See footnote 34part the Syriac language played in Asia from the third to the ninth century of our era, after it had become the instrument of Christian preaching. Like the Greek for the Hellenistic East, the Latin for the West, Syrian became the Christian and ecclesiastical language of Upper Asia.

Even today there are in other countries many thousands of believers who derive their church past from the Assyrian communion and who use the Syriac in their divine services. Political, social, and commercial relations between China and the western nations were carded on many centuries before the population of its capital dedicated the memorial monument. About one hundred twenty years before Christ an official embassy of exploration was sent out by the Chinese emperor to study the kingdoms of the west and to bring greetings to their peoples and rulers. This exploration party returned to relate that they had gone through Bactria, Parthia, Persia, and Ta-Chin (that is, Palestine, the country of Adam’s religion according to the monument). Two hundred years later — or in the days of the apostles — a Chinese general led the victorious regiments of his emperor across Persia to the shores of the Caspian Sea

to the imperial court of China about A.D. 168, and one or two similar embassies about one hundred years later. They also record that about two hundred years later (A.D. 381) more than sixty-two countries of the “western regions” sent ambassadors or tribute to the Middle Kingdom.36If the Chinese traveled so extensively to the west, it is no wonder that Saeki exclaims:

“It would be very strange if the energetic Syrian Christians, full of true missionary zeal, did not proceed to China after reaching Persia about the middle or end of the second century!” (37)

Another authority sees them well settled in China in 508. (38) Thus, there is ample justification to conclude that many true believers were in Asia several centuries before Adam and his associates erected the monument to their church.

BELIEFS OF EARLY CHRISTIANITY IN CHINA

Many documents and historical references tell of the faith held by the Church of the East in China in Adam’s day. Already notice has been made of the prophecy which Isaiah uttered predicting converts in that far-distant land. Testimony has also been used to show that in 481-222 B.C. Jews held important military posts, some becoming provincial governors, ministers of state, and learned professors

Christ, the prophets, and the apostles. In quiet simplicity, accompanied by the minimum of ceremonies, they accomplished an unusual amount of missionary work. The position held by Adam substantiates the splendid organization of the Church of the East, also the strength of its position in China. On the

They had the Apostles’ Creed in Chinese. They had a most beautiful baptismal hymn in Chinese. They had a book on the incarnation of the Messiah. They had a book on the doctrine of the cross. In a word, they had all

See footnote 41literature necessary for a living church. Their ancestors in the eighth century were powerful enough to erect a monument in the vicinity of Hsi-an-fu.

FROM ADAM TO THE MONGOL EMPERORS

The time which elapsed from the Tang dynasty of the days of Adam to the close of the Mongolian conquest was about five hundred years. During that time the nature of the development of the Church of the East in the land of the Yellow River is seen in the character of the clergy, the type of sacred literature used, the life of the believers, the abundant activities of the communities, and the public services rendered by it to the nation. The clergy who led the Church of the East to victory were men of consecration and scholarship. They found the ancient religions of Confu-cianism and Taoism in China entrenched in the affections of the people. Confucius himself upheld polygamy.(42) Confucius was also a spiritist; he ever believed that he was accompanied by the spirit of the duke of Chou

“In the year 1092 of the Greeks (1092-311= A.D. 781) my Lord Yesbuzid, Priest (Pastor) and chor-

It must not be thought, however, that their growth progressed smoothly. Often they met with bitter opposition. Upon the death of one of the great Tang emperors, the throne was occupied during two short reigns by rulers of inferior capacity. One of these favored Buddhism. The Buddhists, seizing this advantage, raised their voices against the Christian religion. In the other reign, inferior scholars of the Taoists, favored by the imperial majesty, ridiculed and slandered Christianity.

“The Christianity of China, between the seventh and the thirteenth century, is invincibly proved by the consent of Chinese, Arabian, Syriac, and Latin evidence.”

See footnote 49

__________________________________________

SEE FOOTNOTE / SOURCE

1. Rawlinson, The Seven Great Monarchies of the Ancient Eastern World, vol. 2, p. 444.

2. See Saeki, The

3. Sansom, Japan, pp. 80, 81; Saeki, The

4. Sansom, Japan, pp. 81-84.

5. It was the writer’s privilege to examine the stone firsthand, having made an airplane trip there for that purpose. We took particular pains to take pictures of this renowned memorial and to study the city with its surrounding country.

6. Saeki, The Nestorian Monument in China, pp. 14, 15.

7. Huc, Christianity in China, Tartary, and Thibet, vol. 1, pp. 45, 46.

8. Gordon, “World Healers,” p. 147.

9. Saeki, The Nestorian Monument in China, p. 175.

10. Yule, The Book of Ser Marco Polo, vol. 1, p. 191, note 1.

11. Ibid., vol. 1, p. 191; also Beal, Buddhists’ Records of the Western World.

12. Monier-Williams, Indian Wisdom, p. 49.

13. See the author’s discussion in Chapter 2, entitled, “The Church in the Wilderness in Prophecy.”

14. Sansom, Japan, p. 133.

15. Gordon, “World Healers,” pp. 31, 32, 229.

16. Ibid., p. 27.

17. Geikie, Hours With the Bible, vol. 6, p. 383, note 1; Old TestamentSeries on Isaiah 49:12; Encyclopedia Brittanica, 9th and 11th eds., art.“China”; M’Clatchie, “The Chinese in the Plain of Shinar,” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, vol. 16, pp. 368-435.

18. Pott, A Sketch of Chinese History, 3d ed., p. 2.

19. Lacouperie, Western Origin of Early Chinese Civilisation, pp. 9, 12.

20. Gordon, “World Healers,” p. 54.

21. Saeki, The Nestorian Monument in China, pp. 39, 40.

22. The attendant at the “forest of tablets” in Changan showed the writer a stone slab with a face carved upon it which, he claimed, was believed to be the face of the apostle Thomas.

23. Arnobius, Against the Heathen, found in Ante-Nicene Fathers, vol. 6, p.438.

24. Smith, The Oxford History of India, p. 122.

25. Forsythe, Journal of the Royal Geographic Society, vol. 47, p. 2.

26. Yule, The Book of Ser Marco Polo, vol. 1, p. 192, note.

27. Johnson, Journal of the Royal Geographical Society, vol. 37, p. 5.

28. Quatremere, Notices des

29. Rawlinson, The Seven Great Monarchies of the Ancient Eastern World,vol. 2, p. 444.

30. M’Clatchie, Notes

31. Finn, The Jews in China, p. 23.

32. M’Clatchie, A Translation of the Confucian Classic of Change, p. 118.

33. Harlez, Le Yih-King: A French Translation of the Confucian Classic onChange, p. 72. Translated by this author from a French version (using the important footnote of M. de Harlez). Many translators of the Chinese render the “culminating day” differently. Most all agree, some at length, that this section of the Yih-King, the oldest Chinese book,

34. Renan, Histoire General et Systeme Compare des Langues Semitiques,p. 291.

35. Smith, The Oxford History of India, p. 129.

36. Saeki, The Nestorian Monument in China, pp. 41, 42.

37. Ibid., p. 43.

38. Lloyd, The Creed of Half Japan, p. 194, note.

39. Gordon, “World Healers,” p. 54.

40. Saeki, The Nestorian Monument in China, pp. 162, 255; see also pp.186, 187.

41. Saeki, The Nestorian Monument in China, pp. 70, 71.

42. Li Ung Bing, Outlines of Chinese History, pp. 50, 51.

43. Sansom, Japan, p. 111.

44. Huc, Christianity in China, Tartary, and Thibet, vol. 1, pp. 167, 221.

45. Cable and French, Through Jade Gate and Central Asia, pp. 136-138.See Gordon, “World Healers,” for a study of the idolatry of Buddhism.

46. Saeki, The Nestorian Monument in China, p. 175.

47. Mingana, “Early Spread of Christianity,” Bulletin of John Ryland’sLibrary, vol. 9, pp. 325, 338.

48. Mingana, “Early Spread of Christianity,” Bulletin of John Ryland’sLibrary, vol. 9, pp. 308-310.

49. Gibbon, Decline