In the sixth century, according to the report of a Nestorian traveler, Christianity was successfully preached to the Bactrians, the Huns, the Persians, the Indians, the Persarmenians, the Medes, and the Elamites: the barbaric churches, from the Gulf of Persia to the Caspian Sea, were almost infinite… The zeal of the Nestorians overleaped the limit which had confined the ambition and curiosity both of the Greeks and Persians. The missionaries of Balch and Samarcand pursued without fear the footsteps of the roving Tartar…. In their progress by sea and land the Nestorians entered China by the port of Canton.

See footnote 1

PROMINENT among the dauntless leaders who spread the faith from

the Tigris eastward is Aba (c. A.D. 500-575). He is identified with that great church which has been called the Waldenses of the East. For centuries the followers of Jesus in Asia generally were called

Persian commanders in chief did not distinguish between the papal Christianity of the Roman Empire and the Church of the Messiah. All Christians were alike to them whether the believers were of Persia or of Rome. The Iranian lords feared collusio

authorities, had imbibed much of the lure and philosophy of Mithraism, was very

resentment against the Christians would run something like this:

“They despise our sun-god. Did not Zoroaster, the sainted founder of our divine beliefs, institute Sunday one thousand years ago in honor of the sun and supplant the Sabbath of the Old Testament which the Jews in our land then sanctified? Yet these Christians have divine services on Saturday. They desecrate the sacred earth by burying their dead in it and pollute the water by their ablutions. They refuse to go to war for the shah-in-shah; and they preach that snakes, scorpions, and creeping things were created by a good God.”

The intention of Shapur II to deal effectively with the followers of theNew Testament did not stop with the death of Shimun. The next catholicos, elected as his successor, followed him to a martyr’s grave. And when another head of the church was chosen and was also put to death, the office remained vacant for twenty years.

Advocacy of an unmarried clergy never had the ascendancy in the Church of the East. Such houses of celibate life would not have been able to endure in Persia. The persecution was bitter enough against the eastern theological training centers, and it was furious against unmarried clergy. The Mithraic faith was strong in advocating marriage and the presenting of children to the state who could serve in the army and be of

being made to the king, the bishop was ordered to restore the building and to make good all damage that had been done. When the bishop refused, Yazdegerd I threatened to destroy every church in his dominion. Such orders were issued and were carried out eagerly by the Zoroastrians inflamed with jealousy against the believers. Before long the destruction of the churches developed into ageneral persecution. Yazdegerd I died in 420, and his son, Bahram

church.(5) Clergy and laity alike were subjected to the most horrible tortures.

Their feet were bored with sharp irons, and some experienced what is called the“nine deaths,” where bit by bit their bodies were cut to pieces. It was quite common under the different monarchs to confiscate the wealth of the well to do and to pillage their homes. Had there been no state Christianity in the Roman Empire, probably in Persia there would not have been persecutions of Christianity. Zeno, the Roman emperor, closed the Assyrian church college at Edessa because it did not agree with the theological views then prevailing in the state religion

When we remember how much of the culture of medieval Europe was to come to her through the Saracens, and that the ‘Nestorians’ were the teachers of the Saracens, one is set asking whether Oxford, Cambridge, and Paris do not owe an unsuspected debt to Bar-soma, though the road from Nisibis to those centers may run through Bagdad and Salamanca.6

See footnote 6

Persia later became tolerant of Christianity; liberty was increased

there while it was vanishing in Europe. If Mohammedanism had not conquered Persia, the Christians would probably have gained complete religious liberty.

PERSIAN CHRISTIANS ESCAPE THEOLOGY OF ROME

The Christianity of Persia existed not only as a challenge to Mithraism, but it also differed widely from the ruling church in the Roman Empire. The forty years of persecution by Shapur II made impossible any contact between the believers in the two dominions. The revolutionary events which centered in the Council of Nicaea and in the angry controversies which followed that gathering were unknown to the churches beyond the Euphrates. They had no part in the fierce disputes concerning the Godhead. They had grown in strength and had performed miracles inspreading the gospel eastward before the contest arose over Nestorius. Nestorianism, according to Samuel Edgar, is a dispute about words

To note some points of difference between the Church of the East and the Papacy, it may be observed that the first rejected the use of images, and interposed no mediator like the Virgin Mary between God and man. The Church of the East also dispensed with candles, incense, relics, and many other usages of imperial Christianity. They had a different Bible than that of Rome; for their

They have no doctrine of transubstantiation, no purgatory; they do not sanction Mariolatry or image worship; nor will they even allow icons to be exhibited in their churches. Men and women take the communion in both kinds. All five orders of clergy below the bishops are permitted to marry.

See footnote 11

MISSIONARY EXPANSION FROM PAPAS TO ABA

“In the early Christian centuries there was a system of roads and posts between the cities of central Asian plains as lately shown by the recovery of documents in some of the unearthed cities), and there was no pass unknown to the Chinese pilgrims — not only the direct routes but all the ways which linked up the Buddhist centers.”

See footnote 12

“When the Persian King, Kawad (A.D. 498), because of rebellions in his kingdom, twice took refuge with the Huns and Turks, he found Christians there who helped him to reconquer his land.”

See footnote 13

When he had regained his throne, he killed some Mithraists, incarcerated others, but was benevolent toward the Christians because a company of them rendered service to him on his way to the king of the Turks. (14) About this same time the Assyrian Christians were credited with having taught the Turks the art of writing in their own language. In commenting upon their expansion eastward, Wigram indicates their influence over Tibet:

“The seventh century was the period of missions to China

See footnote 15; and the strangely Christian-like ceremonial of modem lamas was quite possibly borrowed from Assyrian sources.”

The scholar, Alexander von Humboldt, reveals how thorough were the education and organization in the Church of the East before Aba. He also shows how this same church taught arts and sciences to the Arabs:

It was ordained in the wonderful decrees by which the course of events is regulated, that the Christian sects of Nestorians, which exercised a very marked influence on the geographical diffusion of knowledge, should prove of use to the Arabs even before they advanced to the erudite and contentious city of Alexandria, and that, protected by the armed followers of the creed of Islam, these Nestorian doctrines of Christianity were enabled to penetrate far into Eastern Asia. The Arabs were first made acquainted with Greek literature through the Syrians, a kindred Semitic race, who had themselves acquired a knowledge of it only about a hundred and fifty years earlier through the heretical Nestorians. Physicians, who had been educated in the scholastic establishments of the Greeks, and the celebrated school of medicine founded by the Nestorian Christians at Edessa in Mesopotamia, were settled at Mecca as early as Mohammed’s time, and there lived on a footing of friendly intercourse with the Prophet and Abu-Bekr.

See footnote 16

In 549 the White Huns, inhabiting the regions of Bactria, and the Huns on both the north and south banks of the Oxus River, sent a request to Persia to Catholicos Aba that he would ordain for them a director. The Persian king was astonished to see these representatives of the thousands of Christians in that distant land coming to him; and being amazed at the power of Jesus, he concurred. The spiritual director was ordained, and here turned with the mission

Turkish stock with an infusion of Mongolian

of the Council of Nicaea.21 There is no doubt that the fierce forty-year persecution of King Shapur II of Persia hurried many Christians away into India. One supreme head of the church wrote that the book of Romans was translated into Syrian (c. A.D. 425) with the help of pastor Daniel from India

“The famous Bar Somas, bishop of Nisibis from 435 to 489 A.D., did much to spread Nestorian teaching in the East —in central Asia, and then in China.”

See footnote 24

Mingana reveals the civilizing influences of these missions:

“We need not dwell here on the well-known fact that the Syriac characters as used by the Nestorians gave rise to many central Asian and Far Eastern alphabets such as the Mongolian, the Manchu, and the Soghdian.”

See footnote 25

These facts reveal that the missionaries of the church in Asia were the makers of alphabets as well as the creators of

In the sixth century, according to the report of a Nestorian traveler, Christianity was successfully preached to the Bactrians, the Huns, the Persians, the Indians, the Persarmenians, the Medes, and the Elamites. The barbaric churches, from the Gulf of Persia to

See footnote 26theCaspian Sea, were almost infinite; and their recent faith was conspicuous in the number and sanctity of their monks and martyrs. The pepper coast of Malabar and the isles of the ocean, Socotraand Ceylon, were peopled with an increasing multitude of Christians; and the bishops and clergy of those sequestered regions derived their ordination from thecatholicos of Babylon.

ABA COMES TO THE CATHOLICATE

Aba came to the

The work of organization and reform had not been accomplished too soon; for not many weeks can have elapsed after the patriarch’s return from his tour when his persecution at the hands of the Magi began — a trial that was to continue until his death. (27) Naturally it was not long before an “apostate” so conspicuous as the patriarch was attacked; he being accused to the king by the mobed mobedan in person, and charged with despising the national “din,” and with proselytizing…The patriarch was arrested, and tumultuously accused as an apostate and a proselytizer, both of which charges he fully admitted, and was threatened with death.28Aba was given no opportunity of defending himself, but was declared guilty and worthy of death. On this he appealed to the king, who had by this time (for the proceedings took time) returned from the war to Seleucia.Chosroes heard the case, the mobeds demanding the death of the enemy of ‘the religion,’ and called on the patriarch for his answer.‘I am a Christian,’ he said; ‘I preach my own faith, and I want every man to join it; but of his own free will, and not of compulsion. I use force on no man; but I warn those who are Christians to keep the laws of their religion.’ ‘And if you would but hear him, sire, you would join us, and we would welcome you,’ cried a voice from the crowd. It was one Abrudaq, a Christian in the king’s service, and the words, of course, infuriated the mobeds, who demanded the death of the blasphemer.(29) Still a false accuser was found and produced in court — where he broke down utterly and ignominiously, confessing himself that all his accusations were false. Such an end to such a charge against aman who had done Aba’s reforming work is as high a testimony tothe character of that work as could well be given.(30)

See footnotes 27-33

Shortly afterwards Chosroes met Aba in the street (the patriarch was apparently allowed a measure of personal liberty), and to the horror and rage of the Magi returned his salute with marked friendliness, and summoned him to an audience. Here he told him frankly that, as a renegade, he was legally liable to death…. “But you shall go free and continue to act as catholicos if you will stop receiving converts, admit those married by Magian law to communion, and allow your people to eat Magian sacrifices.” Obviously the mobeds had been influencing the king; but the royal offer sheds an instructive light on the rapid growth of the Church, and on the position of the patriarch as recognized head of his melet. To the terms, however, Aba could only return his steadfast nonpossumus, and the king, annoyed at the attitude, ordered him toprison under the care of the Magi. This was equivalent to asentence of death, though it was probably not so intended; for when he was in prison it would be easy to dispatch him by the hand of some underling, and represent that an act of possibly mistimed zeal towards a notorious apostate ought not to be judged severely.31Amid the passionate grief of all Christians he departed, and reached the appointed province; but the local rad, Dardin (a man selected for his notoriously hard character), soon showed such respect and regard for the patriarch that he was removed thence, and sent to‘Sirsh,’ the very center and stronghold of Magianism…. Here his confinement was purposely made very severe at first, in the undisguised hope that his death would be caused by it; and the hard winters of the high Persian plateau must have been a further trial to one bred in the land of Radan, which is practically the Babylonian plain. Later, however (perhaps in response to a hint from the court), he was allowed to live in a house of his own, where he furnished a room as a church, and his friends were allowed to visit him. Here for seven years he continued in a captivity which may without irreverence be compared to that of St. Paul; and acted as patriarch from his prison in the Magian stronghold. He consecrated bishops, reconciled penitents, governedby interviews and correspondence. Men came in numbers to see him, and ‘the mountains of Azerbaijan were worn by the feet of saints’ who came either on Church business, or on what tended to become a pilgrimage to a living saint.(32) Finally his persecutors, disappointed no doubt at the failure of their double plan, to deprive him of his power or to compass his death, determined to be done with him forever. An assassin washired, one Peter of Gurgan, an apostate Christian priest; and a plotformed for the murder of Aba, who, it was to be explained, hadbeen cut down in attempting to make his escape. The plot failed, and was discovered, and the wretched instrument fled. Aba, however, recognized that the attempt would be repeated, perhaps with better fortune, and took a bold resolution. He left his place of exile with one or two companions, but went, not to any place of concealment, but straight to Seleucia and the king, before whose astonished gaze he presented himself. The Magians, were of course, delighted, thinking that their enemy was at last delivered into their hands. The patriarch was, of course, arrested; and the amazed Chosroes asked what he expected, after thus flying in the face of the royal command. Fearlessly Mar Aba replied that he was the king’s servant, ready to die if that was his will; but though willing to be executed at the king’s order, he was not willing to be murdered contrary to his order. Let the king of kings do justice! No appeal so goes home to an oriental as a cry ‘to the justice of theking.’…Now he heard the stream of accusations that the Magians pouredout, and then addressed the patriarch. ‘You stand charged with apostasy, with proselytizing, with forcing your melet to abstain from marriages that the state accepts, with acting as patriarch in exile against the king’s order, and with breaking prison — and you admit the offenses. All the offenses against the state I pardon freely; as a renegade from Magianism, however, you must answer that charge before the mobeds. Now, as you have come of your own accord to the king’s justice, go freely to your house, and come to answer the accusation when called upon.’ The decision shows atonce the strength and weakness of the king: he could pardon offenses against himself, and he could respect a noble character; buthe dared not defy the Magian hierarchy….Still fear of the mobeds prevailed with the king, and he allowed them to arrest the patriarch and convey him to prison secretly, for fear of riot; though it must be owned that he gave strict orders that he was on no account to be killed. For months Aba remained in prison and in chains; though, as is usual in Oriental prisons, his friends were allowed to visit him (probably by grace of the great power Bakhshish), and he was allowed even to consecrate bishops while in confinement. Still a captive, he was obliged to accompany the king on the whole of his ‘summer progress;’ though at every halting place Christians crowded to see him and receive his blessing, and to petition the king for his release. Even mobeds respected him, and promised to intercede for his pardon if he would but promise to make no more converts. Finally, soon after the royal return to Seleucia, his patientconstancy was victorious. Chosroes sent for him, and released him, absolutely and unconditionally. It is true that when the king left the city, soon after, the mobeds pounced on their prey, and the patriarch found himself in prison once more; but though Chosroes might hesitate long, he was not the tool the mobeds imagined him to be, and this open contempt of the royal decree roused him.A sharply worded order for the instant release of the prisoner came back, and Mar Aba, worn in body and broken in health, but yet victorious, came out once more, and finally, from his prison. Nine years of persecution and danger had been his portion, but he had endured to the end, and he was saved.(33)

Shortly after this Aba passed away. He is presented as a type of those patriarchs who ruled the Church of the East during the eventful days when the religion of Mithra dominated the throne of Persia. Aba was called to his heavy task in an hour when the cause needed the hand of a strong leader.

FROM ABA TO THE MOSLEM CONQUEST

The individual history of the successors of Aba in the two centuries which elapsed between his

Sir E. A. Wallace Budge, in commenting on the controversy over the two natures of Christ, writes:

“It is very difficult to find out exactly what Nestorius thought and said about

See footnote 38them, because we have only the statement of his enemies to judge by.”

The interference of the state in religion had put things on

“After a period of thirteen hundred and sixty years…the hostile communions still maintain the faith and discipline of their founders. In the most abject state of ignorance, poverty, and servitude, the Nestorians and Monophysites [another name for the Jacobites] reject the spiritual supremacy of Rome, and cherish the toleration of their Turkish masters.”

See footnote 39

While it would be incorrect to say that the Jacobites and the Church of the east agreed in doctrines, organization, and practices, nevertheless their differences fundamentally were not great. The Church of the East, growing up in an entirely Oriental environment, never was under Rome. The Monophysites, in all their branches — Abyssinians, Copts of Egypt, Jacobites, and Armenians — though citizens of the empire until their break with Rome, early refused to go along with the religion of the Caesars. The believers located in the valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates escaped many of the beliefs and practices which the Papacy later adopted. (40) When, from about 650, both bodies passed more or less under Mohammedan rulers, their afflictions were less severe than those experienced by evangelicals in the Gothic ten kingdoms of western Europe when brought under papal rule. Assyrian Christians and Jacobites suffered comparatively little at thehands of the Moslems, but later much more so at the hands of the Jesuits. These later afflictions had a tendency to draw them together. As an illustration, witness the Assyrian Christians of

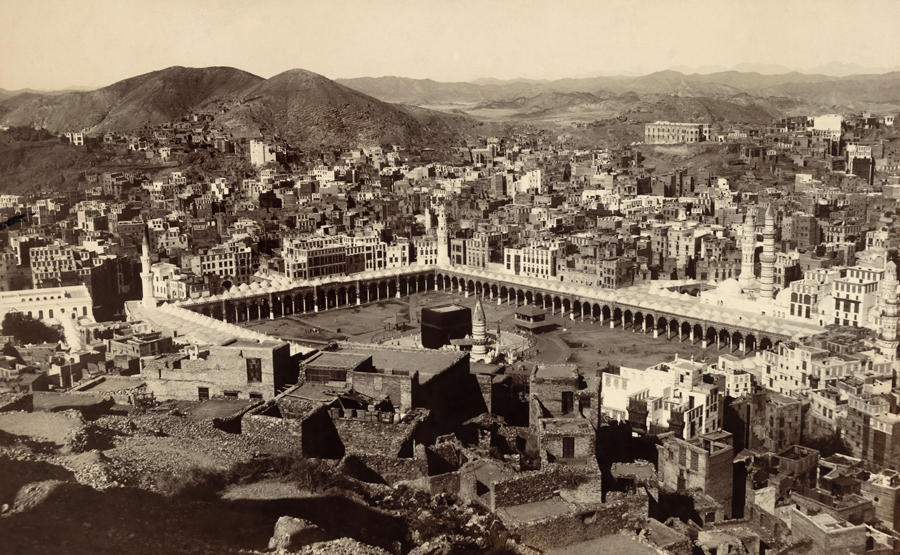

RISE AND CONQUESTS OF THE MOHAMMEDANS

Like the smoke out of the bottomless pit,(Revelation 9:1-3.) darkening thesun and the air, the new religion of Mohammed suddenly issued fromArabia. Like a whirlwind from the desert, it swept furiously over rivers and plains until all of western Asia, northern Africa, and the southern extremities of Europe had been conquered. Three factors contributed to thesudden and amazing conquests of the Arabians. The first

was the new national awakening among the Arabs. The second was the exhaustion of the Roman and Persian Empires caused by four centuries of constant warfare between themselves plus the gigantic invasions of the Goths which had overrun the western provinces of Rome. The third was Mohammed himself. In the days of Aba and his

______________________________________________________________________________

FOOTNOTE / SOURCE

- Gibbon, Decline

and Fall of the Roman Empire, ch. 47, par. 30. - Foakes-Jackson, The History of the Christian Church, p. 184.

- Foakes-Jackson, The History of the Christian Church, pp. 184, 185.

- Newman, A Manual of Church History, vol. 1, p. 296.

- O’Leary, The Syriac Church

and Fathers, pp. 83, 84. - Wigram, Introduction to the History of the Assyrian Church, p. 167.

- Edgar, The Variations of Popery, p. 62.

- Before the writer visited the bishop of the cathedral in Trichur, India, he had been informed that it was a Nestorian church. When, however, he sat at the table with the bishop, this official declared that not only he but all the directors belonging to his denomination rejected the

nameNestorian . - O’Leary, The Syriac Church

and Fathers, p. 46. - Milman, The History of Christianity, vol. 2, pp. 248, 249.

- Adeney, The Greek and Eastern Churches, pp. 496, 497.

- Gordon, “World Healers,” pp. 231, 232.

- Mingana, “Early Spread of Christianity,” Bulletin of John Ryland’sLibrary, vol. 9, p. 302.

- Ibid., vol. 9, p. 303.

- Wigram, Introduction to the History of the Assyrian Church, p. 227.

- Humboldt, Cosmos: A Sketch of a Physical Description of the Universe, vol. 2, p. 208.

- Mingana, “Early Spread of Christianity,” Bulletin of John Ryland’sLibrary, vol. 9, pp. 304, 305.

- Mingana, “Early Spread of Christianity,” Bulletin of John Ryland’sLibrary, vol. 9, p. 316.

- Ibid., vol. 9, p. 317.

- Gordon, “World Healers,” p. 146.

- Buchanan, Christian Researches in Asia, pp. 141, 142.

- Mingana, “Early Spread of Christianity,” Bulletin of John Ryland’sLibrary, vol. 10, p. 459.

- Yule, The Book of Ser Marco Polo, vol. 2, pp. 407-409, with notes.

- Saeki, The Nestorian Monument in China, p. 105.

- Mingana, “Early Spread of Christianity,” Bulletin of John Ryland’s Library, vol. 9, p. 341.

- Gibbon, Decline

and Fall of the Roman Empire, ch. 47, par. 30. - Wigram, Introduction to the History of the Assyrian Church, p. 199.

- Ibid., p. 200.

- Ibid., p. 201.

- Ibid., p. 202.

- Wigram, Introduction to the History of the Assyrian Church, pp. 202,203.

- Ibid., pp. 203, 204.

- Wigram, Introduction to the History of the Assyrian Church, pp. 204-207.

- Yule, The Book of Ser Marco Polo, vol. 2, p. 409, note 2; also Gordon, “World Healers,” p. 466.

- Realencyclopedie fur Protestantische Theologie und Kirche, art.“Nestorianer”; also, Bower, The History of the Popes, vol. 2, p. 258, note 2.

- Couling, The Luminous Religion, p. 44.

- When the writer was in Beyrouth, Syria, he visited the Jacobite bishop. A series of questions were asked the church leader regarding his people and their history. The last remark of the bishop was that his church had

anath-ematized Nestorius. He admitted that the Papacy had anathematized the Jacobites. - Budge, The Monks of Kublai Khan, Emperor of China, p. 37.

- Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, ch. 47, par. 28.

- Edgar, The Variations of Popery, pp 60-67